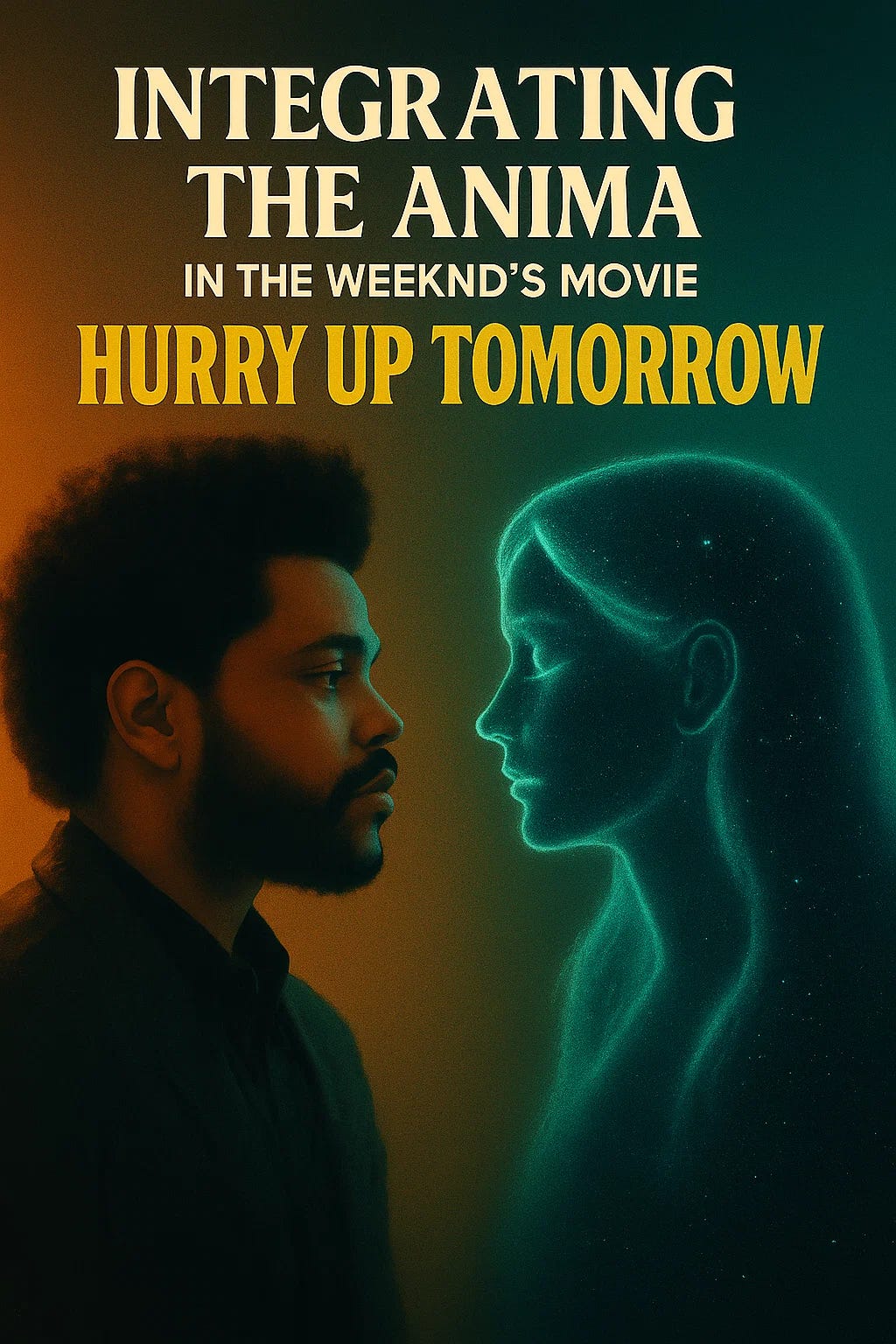

The Anima Must Be Heard: A Jungian Reflection on The Weeknd’s Inner World and My Own

“Before she unties him, the anima has to burn the house down.”

The opening scene of Hurry Up Tomorrow isn’t just symbolic — it’s prophetic. A woman pours gasoline across the floor and watches it ignite, destroying the home behind her. This is no ordinary woman. She is the anima — the inner feminine force in a man’s psyche that, according to Carl Jung, rises up when the ego has grown too rigid, too performative, too disconnected from the soul.

Contrary to my preconceived notions of the “feminine,” the anima doesn’t symbolize pure, unconditional love (the way Jesus does, for example). When she isn’t integrated — when she is ignored, repressed, or replaced by blind ambition — she doesn’t fade away. She roars; she riots.

“The anima is not just a consoling mother or a beautiful muse. She is also a temptress, a sorceress, and a destroyer. Her purpose is to initiate transformation — and sometimes she must destroy in order to create.”

— Carl Jung

Watching this film, I didn’t just observe a narrative unfolding on screen. I saw my own story reflected back at me.

In 2021, I hit an emotional rock bottom. After a painful romantic rejection that followed a string of similar disappointments, I felt completely shattered. My confidence dissolved. I became consumed by confusion, desperation, and pain. I had been unconsciously chasing a pattern: idealizing women, falling into infatuation, and placing them on a pedestal. Jung describes this as a classic symptom of an unintegrated anima: we project our inner feminine onto external figures and mistake that projection for love.

“The anima, when projected, has the effect of creating a fascination that is both compelling and misleading. The man is no longer dealing with a real woman but with a psychic image.”

— Carl Jung

Jung warned that when a man hasn’t integrated his anima, he becomes especially vulnerable to emotional chaos through romantic infatuation. The woman becomes a symbol of everything he lacks internally — beauty, mystery, love, salvation. She becomes, unconsciously, the answer to his soul’s longing. And yet, no woman can carry that weight. No one outside us can.

That was me for much of my early adult life. I chased women hoping they would fix the pain I couldn’t name. I glorified them. I believed they would complete me. And every time they didn’t — every time they withdrew or rejected me — it reinforced the deep wound I was trying to escape. The rejection wasn’t just personal. It felt existential.

That breakup in 2021 was a wake-up call. I was done running in circles. I started going to therapy, and eventually psychedelic-assisted therapy (after hearing people like Joe Rogan and Jordan Peterson rave about itss transformative power), where I began to look inward for the first time. In my first MDMA therapy session, I saw clearly some of the origins of this pain — my childhood, my relationship with my mother, and the deep stress I had internalized from her. Her stress had become my stress. I had never learned to regulate my nervous system or to be kind to myself. I had only learned to achieve.

My early 20s have been marked by professional success: op-eds in major newspapers, viral essays, podcasts with major public figures like Jordan Peterson and multiple shoutouts by Joe Rogan, the #1 podcaster in the world. On the surface, I was thriving. But inside, I was hollow. I had launched a fast-moving career in journalism, but I was using ambition to fill a void. Jung might say I was clinging to the masculine principle of order, structure, and achievement — while my inner feminine was starving for attention, compassion, and truth.

Like Abel in the film, I was relentlessly pushing forward. More essays. More influence. More productivity. But the cost was high. By 2022, my body began to revolt. I developed chronic digestive issues, chest pain, and anxiety. Doctors called it GERD. But as I read the works of Alan Gordon and Dr. Howard Schubiner, I began to understand these symptoms as psychosomatic — my nervous system was in a constant state of fear and dysregulation.

And like The Weeknd losing his voice on stage, my body forced me to stop. To listen. To feel.

In my third, most recent MDMA therapy session, I had a revelation: I had been living my life through a rigid, hypermasculine structure of goals, discipline, and constant forward motion — thinking peace would come once I achieved enough.

But peace is not a reward. It is a practice. It is presence. It is the voice of the anima — the part of me that just wanted to feel, to breathe, to love.

This is what Jung means when he speaks of the integration of the anima. She is not to be chased or idealized. She must be listened to. Honored. Felt. The anima teaches us to reconnect with vulnerability, emotion, care, play, beauty, intuition, and love — without abandoning masculine strength and order.

Serendipitously, just days after watching the film, I heard for the first time Jordan Peterson explain Jung’s concept of the anima on Joe Rogan’s podcast.

Peterson’s quote from the podcast on what the integration of the anima means in a man’s maturation process:

“You discover the utility of empathy, compassion, kindness, mercy and care while still being able to deal out justice... That’s the integration.”

But he also warned:

“It’s hard for those who are completely disaffected and angry about it.”

Integration isn’t easy. It often begins in collapse. For me, it began in heartbreak. For The Weeknd, it began in silence and panic on stage. For many men, it begins when their coping mechanisms stop working.

But the journey is worth it. A few days after watching the film, I went out dancing. Using Joe Dispenza’s re-wiring method, I practiced stepping into a new identity: someone who is already enough. Someone who doesn’t need women to validate his worth. That night, I met two women who happened to be huge fans of The Weeknd. I went up and introduced myself and we got along right away. We danced, we laughed, and we talked late into the night. One of them told me, "More men should approach women the way you did."

And what struck me most wasn’t even the connection itself — it was how I felt in that connection. For the first time in a long time, I wasn’t operating from a place of lack. I wasn’t trying to impress or win someone over. I was just being me. Present. Playful. Whole.

This might seem like a small social moment, a night out like any other. But for me, it was seismic. Because I’d spent so much of my life approaching women from a place of woundedness and scarcity. I would constantly feel less-than, inferior, desperate for approval or affection. I would silently believe I was unworthy of their attention, and then overcompensate by trying too hard, or spiraling into anxiety when I sensed disinterest.

In those moments, I wasn’t meeting them as an equal. I was meeting them as a beggar at the temple of the feminine. And when they didn’t reciprocate, I’d collapse into the familiar pit of self-doubt, reinforcing the narrative that I wasn’t enough.

Carl Jung wrote that the man who has not integrated his anima is prone to falling in love in ways that feel magical and overwhelming, but are ultimately projections. He believes he has met her — the ideal, the answer, the missing piece. But what he has actually encountered is his own inner feminine being projected onto a flesh-and-blood person who cannot possibly fulfill that role.

This is the trap I had fallen into for years. I wasn’t just attracted to women — I was looking for salvation. And that is too heavy a burden to place on another person. The women I idolized could never be what I unconsciously needed them to be.

That night after watching The Weeknd’s film, something shifted. I met those two women not with hunger or hope for validation, but with grounded presence. I didn’t need them to complete me. I was enjoying myself. I was living in the moment. I cracked jokes, I danced with ease, and I opened up without trying to perform.

Later, walking to McDonald’s together at 2am, it felt like a different version of me had come alive — not the old pattern of chasing or projecting, but a new way of relating. A way that felt honest. Joyful. Human.

And it made me reflect on Abel’s own arc in the film. He’s pursuing relationships from inner lack and deficit, not wholeness. It’s the path of the unintegrated anima: seeking completion through others, only to find emptiness again and again. The anima isn’t asking us to chase her. She’s asking us to feel her. To let her in.

And when she’s finally heard in the film, the tone changes entirely. In one of the most pivotal scenes, after Abel loses his voice and collapses into panic, he finds himself alone with the anima in a hotel room. She doesn’t seduce him. She doesn’t try to comfort him in the traditional sense. Instead, she confronts him. She demands his attention. She says things like, “You have to listen to me before I untie you,” and “Be honest with yourself and I’ll set you free.”

She becomes a mirror — not of beauty or fantasy, but of accountability. She forces him to confront the consequences of his avoidance. She plays back his own songs like Blinding Lights and Gasoline, not as entertainment, but as revelations. She says these songs were born of heartbreak, emptiness, separation, and codependence. Then she asks him the brutal questions: “How much is this about them? Are you the toxic one?”

This is the anima in her rawest form — not soothing, not passive, but unrelenting in her demand for truth. She’s not there to make him feel better. She’s there to make him feel everything. The guilt, the loneliness, the confusion, the emotional wreckage he’s left in his wake.

When he resists, she pushes further. He tries to escape, tries to pay her off, tries to joke it away. But none of it works. She’s not going anywhere until he stops running from himself.

And in doing so, she breaks through his dissociation. She brings him back to the part of himself he abandoned: the emotional core. The part capable of love, of grief, of healing. The inner child he sees huddled by a fire. The softness that ambition tried to annihilate.

She doesn’t free him until he’s willing to feel. That is the essence of integration. And that’s why this film, for all its surreal chaos, holds such deep psychological truth.

The final moments of the film drive this point home. After the symbolic death of the manager — the embodiment of his toxic ambition — we are abruptly brought back to reality. Abel is seen alone in his dressing room, sitting silently before a mirror. The fantastical journey he has just undergone — the confrontation with the anima, the fire, the dreamlike encounters, even the manager’s death — is revealed to be a symbolic experience within his own psyche.

It becomes clear: none of it was literally real. It was a psychological journey. An internal reckoning.

As he prepares to go on stage, the quiet lingers. He doesn't look triumphant. He doesn't look broken either. He looks... changed. A little more aware. A little more whole. The film doesn't end with him performing or explaining what happened. It ends in silence and subtlety — a man facing himself.

And that, perhaps, is the most honest ending of all. Because the journey of integration isn’t about a sudden breakthrough or external validation. It’s about noticing the shift. It’s about returning to your life — the same routines, the same roles — but bringing something different into it. A deeper presence. A deeper honesty.

It’s what I hope to embody more and more in my own life.

Not the chase.

But the integration.